Notice of Exempt Solicitation

Name of Registrant: NIKE, Inc.

Name of Person Relying on Exemption: Shareholder

Association for Research and Education (SHARE)

Address of Person Relying on Exemption: Unit 401, 401 Richmond Street

West, Toronto, ON M5V 3A8, Canada

Date: August 12, 2024

Written materials are

submitted pursuant to Rule 14a-6(g) (1) promulgated under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Submission is not required of this filer

under the terms of the Rule but is made voluntarily.

This is not a solicitation of authority to vote

your proxy.

Please DO NOT send us your proxy card as it

will not be accepted

Nike, Inc.

Shareholder Proposal

Number 6 Regarding Worker-Driven Social Responsibility

We urge shareholders

to vote FOR Proposal Number 6 – Shareholder Proposal regarding worker-driven social responsibility – at the Nike, Inc’s

(“Nike’s” or the “Company’s”) Shareholder Meeting on September 10, 2024. The Shareholder Proposal

was filed by the Domini Impact Equity Fund, Trillium Asset Management, the Shareholder Association for Research and Education (“SHARE”),

Triodos Asset Management, CCLA and PGGM.

The Proposal asks Nike to:

Publish a report

evaluating how implementing worker-driven social responsibility principles and supporting binding agreements would impact the Company’s

ability to identify and remediate human rights issues in sourcing from high-risk countries.

|

Summary

Nike’s sourcing practices in high-risk countries

expose the company to operational disruptions, legal liabilities, and reputational damage, which, if inadequately managed, could have

adverse impacts on the Company’s revenues thus threatening shareholder long-term value.

The UNGPs – that Nike refers to in its Human

Rights and Labor Compliance Standards – call on companies to implement proportionate human rights due diligence and a differentiated

approach in areas of higher risk. It also emphasizes businesses’ responsibility to ensure effective remedy when adverse human rights

impacts have been identified.

To our knowledge, Nike’s human rights due

diligence practices in supply chains are reliant on social audits. There is growing evidence suggesting that there are systemic challenges

limiting the effectiveness of social audits, thus undermining companies’ ability to effectively uncover and remediate human rights

abuses.

Given the inadequacies of traditional corporate

social responsibility programs and social audits in particular, a growing number of companies are turning to worker driven social responsibility

and binding agreement models which effectiveness have been clearly demonstrated when it comes to increase worker productivity, reduce

risk, and deliver meaningful human rights outcomes.

As public reports of allegations suggest that

Nike’s due diligence practices may be insufficient to prevent labor rights violations and provide effective remediation in high-risk

countries (including Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam), shareholders expect Nike to demonstrate that it has a differentiated approach with

enhanced due diligence to support the Company’s ability to identify and remediate human rights issues in high-risk sourcing countries.

|

1. Nike’s

supply chain exposure to high-risk countries puts shareholders’ long-term value at risk

1.1 Nike’s supply chain is

exposed to high-risk countries where systemic human rights abuses are evidenced

Nike’s global supply chain

includes 1.1 million supply chain workers at 505 factories in 36 countries around the world.1 Its production model has been

built around three pillars - outsourcing to save costs, diversification of production to minimize risks, and corporate social responsibility

to manage its impacts.2

_____________________________

1

https://manufacturingmap.nikeinc.com/

2

https://marketplace.adec-innovations.com/blogs/how-does-nikes-supply-chain-work/

It is well established

that the apparel and footwear industry has grappled with significant social issues associated with poor working conditions in global supply

chains.3 Research shows that the risk of exploitative conditions is the highest in countries where labor laws and enforcement

may be ineffective because of evasion, corruption, weak enforcement, and failure to reach the informal sector.4 More generally,

high-risk countries may include areas of political instability or repression, institutional weakness, insecurity, the collapse

of civil infrastructure and widespread violence. Such areas are often characterized by widespread human rights abuses and violations of

national or international law, especially for vulnerable populations.5 Under such conditions, conventional due diligence practices

like social audits have been ineffective.6 Generally, these markets are characterized by at least one of the following conditions:

lack of equal economic and social opportunity, systematic discrimination against parts of the population, poor management of revenues,

endemic corruption, and chronic poverty.7 In response to the pervasive systemic risks in these environments, Worker-Driven

Social Responsibility (“WSR”) initiatives and binding agreements have emerged as the most effective, evidence-based alternatives

to protect the human rights of supply chain workers from labor rights abuses. These alternatives exist in several of Nike’s high-risk

sourcing countries and will be discussed in section 2.

Many sourcing countries in Nike’s global

supply chain are classified as “high-risk” for labor violations in various country ratings and indexes,8 including

China, Cambodia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Philippines, Thailand and others.9 Pervasive and systemic exploitative labor

practices have been identified in these countries such as hazardous working conditions, low wages and wage theft or repression of union

activities. Nike’s extensive sourcing practices in high-risk countries expose

the company to operational disruptions, legal liabilities, and reputational damage,10 which, if inadequately managed,

could have adverse impacts on the Company’s revenues thus threatening shareholder long-term value.

1.2 Failure to uphold

human rights in its supply chain exposes Nike and its shareholders to legal, financial, reputational, and supply chain resilience risks

that may impact long-term shareholder value

Failure to respect fundamental

human rights in supply chains may expose any company to serious reputational, legal, financial and supply chain resilience risks –

all of which could ultimately affect long-term shareholders’ return.

In particular, the

reputational risk may manifest as threats to a company’s stakeholders’ perception when there is a disconnect between a company’s

performance and stakeholder expectations. This may eventually lead to a correction of perception, especially “when the reputation

of a company is more positive than its underlying reality”. In other words, if “the failure of a firm to live up to its billing”

is revealed, “its reputation will decline until it more closely matches the reality.”11 When materialized, the

reputational risk can negatively impact a company’s revenues, exacerbate regulatory scrutiny and negatively affect a company’s

share price.12

_____________________________

3

https://www.ilo.org/publications/state-apparel-and-footwear-industry-employment-automation-and-their-gender

4

https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/221471546254761057/pdf/Labor-Regulations-Throughout-the-World.pdf

5

https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-due-diligence-guidance-for-responsible-supply-chains-of-minerals-from-conflict-affected-and-high-risk-areas_9789264252479-en.html

6

https://fairfoodprogram.org/worker-driven-social-responsibility/; https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2021-Aug/CBP%202021%20VTW%20FAQs%20%28Forced%20Labor%29.pdf;

https://blog.dol.gov/2022/01/13/exposing-the-brutality-of-human-trafficking;

7

https://d306pr3pise04h.cloudfront.net/docs/issues_doc%2FPeace_and_Business%2FGuidance_RB.pdf;

https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2022/11/cambodia1122web_1.pdf

8

https://worldjusticeproject.org/news/we-measured-labor-rights-142-countries-here%E2%80%99s-what-we-found

;

https://labourrightsindex.org/heatmap-2022/2022-the-index-in-text-explanation/labour-rights-index-2022#autotoc-item-10 ; https://www.ituc-csi.org/global-rights-index ;

9

https://manufacturingmap.nikeinc.com

10

https://wsr-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Nike-Lies-report-July-2024.pdf

https://cleanclothes.org/news/2023/nike-board-executives-under-fire;

https://ourfinancialsecurity.org/2024/07/blog-standing-in-solidarity-with-garment-workers-in-nikes-supply-chain/

11

https://hbr.org/2007/02/reputation-and-its-risks

12

https://www2.deloitte.com/gr/en/pages/governance-risk-and-compliance/articles/reputation-risk.html ; https://www.aon.com/2023-cyber-resilience-report/risk/build-a-plan-to-address-the-perils-of-reputational-risk

; https://www.thefashionlaw.com/visibility-is-central-to-a-successful-supply-chain-heres-what-brands-need-to-know/

Nike is a high-profile brand whose image and reputation

contribute to position the company at the forefront of the athletic apparel industry:

| - | In 2023, Nike ranked 21 out of the 100 most visible brands in America by the Axios Harris Poll 100 reputation

ranking, one position ahead of its competitor, Adidas.13 |

| - | Nike also ranks as the No. 1 brand for all teens in both the apparel and footwear rankings of the Piper

Sandler 2023 Fall Semi-Annual Taking Stock With Teens Survey.14 |

| - | According to the Brand Finance Apparel 50 2023 ranking, Nike continues to be the world’s most valuable

apparel brand and notably has the highest Sustainability Perception Value. According to the ranking, Nike’s “‘Move to

Zero’ sustainability campaign has garnered global attention and enhanced global perceptions of the brand’s sustainability

commitment.”15 |

Nike’s reputation has been damaged as a

result of labor rights abuses in the past. In the mid 1990s, was found to have sweatshop-like conditions and child labour in its factories

in Cambodia and Pakistan, which led to significant public scrutiny. A Stanford University paper noted that the association between Nike’s

image and sweatshops damaged the company’s image to the extent “sales were dropping and Nike was being portrayed in the media

as a company who was willing to exploit workers and deprive them of the basic wage needed to sustain themselves in an effort to expand

profits.”16

At the time, heightened scrutiny also exposed

Nike to legal challenges. For example, a lawsuit was filed in 1998 in a California Superior Court alleging that the company “had

violated state law by misleading customers about the working conditions in its Asian factories”. More specifically, the plaintiffs

argued that Nike has “misrepresented the conditions in their factories and the wages they paid [in order] to protect their profits”.17

Since then, Nike has been subjected to several

formal complaints from advocacy groups relating to labor conditions in its supply chain. For instance, in 2022, twenty-eight Canadian

organizations filed a complaint against Nike Canada Corp. with the Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise, alleging that the

company has supply relationships with several Chinese companies that the Australian Strategic Policy Institute identified as using or

benefiting from Uyghur forced labor. The complaint asserts that “there is no indication that Nike Canada Corp. has taken any concrete

steps to ensure beyond a reasonable doubt that forced labor is not implicated in their supply chain.”18 In 2023, twenty

garment sector unions from Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Sri Lanka - representing garment workers in Nike’s supply chain

at the factory and sectoral levels - have filed complaints with the U.S. National Contact Point for the OECD alleging Nike breaches of

the OECD Guidelines.19 Both cases are pending. If findings of non-compliance are confirmed upon investigations, these issues

could prompt further damage to Nike’s public image, additional scrutiny from regulatory bodies, and harm to investor confidence.

As legislatures’ efforts to protect consumers

have intensified globally over the past few decades, several apparel companies have been further exposed to allegations of green and social

washing. For example, in 2023, a lawsuit was filed against H&M over misleading sustainability marketing practices.20 That

same year, the UK Competition and Markets Authority announced it was investigating Asos, Boohoo and Asda over similar claims.21 In

2021, the Association des Ouïgours de France filed a lawsuit in France accusing Nike of “complicity in the concealment of forced

labor and deceptive business practices”.22

_____________________________

13

https://www.axios.com/2023/05/23/corporate-brands-reputation-america

14

https://www.pipersandler.com/sites/default/files/document/TSWT_Fall23_Infographic.pdf

15

https://brandfinance.com/press-releases/nike-retains-crown-as-worlds-most-valuable-apparel-brand-brand-value-usd31-3-billion

16

https://web.stanford.edu/class/e297c/trade_environment/wheeling/hnike.html#:~:text=Sales%20were%20dropping%20and%20Nike,critics%20on%20May%2018%2C%201998

17

https://media.business-humanrights.org/media/documents/files/reports-and-materials/Chapter5.htm

18

https://core-ombuds.canada.ca/core_ombuds-ocre_ombuds/assets/pdfs/initial-assessment-report_nike-en.pdf

19

https://globallaborjustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/OECD-Fact-Sheet-Nike.pdf

20

https://www.classaction.org/media/commodore-v-h-and-m-hennes-and-mauritz-lp.pdf

21

https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/asos-boohoo-and-asda-greenwashing-investigation

22

https://www.lemonde.fr/m-le-mag/article/2021/02/25/plainte-contre-nike-pour-complicite-de-recel-de-travail-force-des-ouigours-tous-les-reseaux-sont-bons_6071113_4500055.html

Additionally, Nike’s failure to respect

human rights in its supply chain may lead to operational disruptions, such as worker strikes, that may negatively impact the resilience

of its global supply chain. This risk is further exemplified by growing regulations on supply chain due diligence. In the U.S., under

Section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection can issue withhold release orders to detain and hold shipments

when it has reason to believe that the goods were made with forced labor, forced child labor, or prison labor23. If the company

does not implement sufficient safeguards to identify, address, and mitigate such abuses in its supply chain, these risks may negatively

impact the company’s ability to have a resilient supply chain.

As Nike’s brand value and reputation continue

to increase, it becomes more exposed to reputational risk and possibly, by extension, to financial and legal risks and regulatory scrutiny.

Given Nike’s history of reputational damage, it is expected that the board and management ensure the adequacy and effectiveness

of Nike’s human rights due diligence policies and practices in high risk countries given the heightened risk of labor rights violations.

2. Nike's

existing human rights policies and practices appear to be insufficient in addressing gaps and violations within its global supply chain,

particularly with respect to sourcing in high-risk countries. Voluntary codes of conduct and audits are not

an effective instrument to manage human rights risks in high risk sourcing countries where enhanced human rights due diligence is needed.

Nike has made a clear commitment

to respecting human rights in its supply chain. Nike’s Human Rights and Labor Compliance Standards state “[they] consider

the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises as best practice

for understanding and managing human rights risks and impacts.”24 The UNGPs call

on companies to respect human rights, including where a company may cause, contribute, or be directly linked to a violation through a

business relationship.25 Businesses also have a responsibility to ensure remedy when adverse human rights impacts have been

identified.26 The expectations set out in the UNGPs call for proportionate human rights due diligence (“HRDD”),

and a differentiated approach in areas of higher risk, which includes high-risk contexts.27 As Nike notes in its Statement

of Opposition to the proposal, it has a Supplier Code of Conduct (“Supplier Code”) and Code Leadership Standards (“CLS”)

and it monitors compliance with regular internal and external third-party audits. Though Nike’s corporate responsibility

approach was instrumental in establishing several initiatives including the Fair Labor Association and the Better Buying initiative -

we view these as important, but not sufficient interventions to ensure the human rights of workers are upheld and appropriate remedy is

available in high risk countries.

_____________________________

23

https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/comply-chain/steps-to-a-social-compliance-system/step-6-remediate-violations/

key-topic-information-and-resources-on-withhold-release-orders-wros#:~:text=Withhold%20Release%20Orders%20(WROs)%2C,detain%20a%20shipment%20of%20goods

24 https://about.nike.com/en/impact-resources/human-rights-and-labor-compliance-standards

25 UN Guiding

Principles on Business and Human Rights p.13; 18, 19.

26 Ibid p.39

27 https://shiftproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Shift_HRDDinhighriskcircumstances_Mar2015.pdf

2.1. Audits

are an ineffective tool for addressing human rights risks in the supply chain

Credible

reports 28 and investigations have highlighted the weaknesses of audits as a comprehensive tool for managing human rights risks

in high-risk countries. These reviews suggest that audits have systemic challenges to their effectiveness, because, among other reasons,

much of the data is hidden from independent scrutiny, suppliers may be subject to multiple audits from different buyers with varying standards,

and there is little evidence that compliant factories are rewarded with better prices or more orders.29

Social

auditing, a private measure for checking compliance with supplier code of conduct, has grown into a US$300 million industry.30

Audits are generally conducted by a third party that monitors compliance with a set of expectations at a specific point in time, through

announced or unannounced site visits. Audits are best suited for finding observable failures in health and safety systems, and remediation

is focused on addressing the non-compliance (i.e. in documentation or management processes), rather than providing a remedy

to the individual that was harmed to make them whole. Moreover, audits often fail to identify violations of human rights practices

that can be less visible in the absence of trusted private interviews, such as gender discrimination and gender-based violence. Some documented

practices that limit the effectiveness of audits at reducing risks include conflicts of interest, audit-fraud, time and cost pressures

for completing an audit, double-bookkeeping, attempts to hide actual work conditions during the audit, and coaching workers on how to

respond in interviews.31

These

practices have become commonplace, and companies relying on audits should explain how they overcome these weaknesses or how they complement

audits with other tools. In addition to failing to reduce risks of non-compliance, this model of auditing has delivered no improvements

in labor standards in the global apparel supply chain.32

2.2. Public reports

indicate that Nike’s HRDD practices have been insufficient to prevent labor rights violations and provide effective remediation

in high-risk countries

Despite

Nike’s reliance on social audits to monitor compliance with its policies including Supplier Code and CLS, public reports indicate

that Nike’s HRDD practices have failed to identify hazardous working conditions in a factory in Vietnam. Nike’s supplier Hansae

Vietnam had 26 separate social audits showing no rights violations. That same year, an investigation utilizing WSR principles unveiled

extensive wage theft, forced and excessive overtime, excessive temperatures in factory buildings (reaching up to 95 degrees Fahrenheit)

exposure to toxic chemicals and lack of ergonomic seating, violations of workers’ associational rights (managers in charge of the

factory union), and abusive treatment of workers.33

_____________________________

28 https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2022/11/Social_audits_brochure_1122_WEBSPREADS_0.pdf

29 https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/07/us/child-labor-us-companies.html

; https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/28/us/migrant-child-labor-audits.html

;

https://www.msi-integrity.org/not-fit-for-purpose/;

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/oct/10/corporate-auditing-foreign-workers-abuse-claims;

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1399069/000119312522160826/d346877dpx14a6g.htm.

30 https://www.hrw.org/report/2022/11/15/obsessed-audit-tools-missing-goal/why-social-audits-cant-fix-labor-rights-abuses

31 https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2022/11/Social_audits_brochure_1122_WEBSPREADS_0.pdf

32 Kuruvilla

S (2021) Private Regulation of labor standards in global Supply Chains: Problems, Progress and Prospects, Cornell University Press p.11

33 https://www.workersrights.org/factory-investigation/hansae-vietnam/

In addition,

there are at least two ongoing cases indicating that Nike failed to provide adequate remedy that responds to the demands of the impacted

workers. In 2021, the Workers Rights Consortium (“WRC”) reported that Nike supplier Ramatex had improperly dismissed and withheld

compensatory pay from workers at its Violet Apparel factory.34 In response, Nike contended that it had not manufactured at

Violet Apparel for a decade35, ignoring worker testimony, factory records, and photographic evidence showing Nike products

at Violet Apparel as late as 2020. Nike also parroted Ramatex’s reliance on a ruling by the Cambodian Arbitration Council on damages

that was widely regarded as corrupt and a reflection of the deteriorating human and worker rights situation in Cambodia.

Also in

2021, WRC reported similar conduct at another Ramatex supplier, Hong Seng Knitting in Thailand. In response, Nike supported the Ramatex

position that workers voluntarily ceded owed wages to the factory, ignoring documented evidence of coercion and intimidation used against

workers when they attempted to ask for what they were owed under Thai law.36 According to public reports, Nike paid workers

monies they were owed (or facilitated that repayment through Ramatex), and has not changed its position on the Violet Apparel and Hong

Seng Knitting cases and Ramatex is still a Nike supplier.37 All of which may indicate that the Ramatex likely violated Nike’s

Supplier Code of Conduct and compromised Nike’s supply chain oversight and its ability to promote better buying principles and adherence

to its own policies.

2.3.

Worker-driven Social Responsibility and Binding Agreements Deliver Concrete Outcomes

Given

the inadequacies of traditional corporate social responsibility programs and in particular, the limitations of social audits combined

with the urgent need for effective protections for workers’ rights in high risk areas, WSR and binding agreements have emerged as

more effective vehicles to promote comprehensive HRDD processes. Indeed, WSR models have been recognized by the United Nations Working

Group on Business and Human Rights as “the international benchmark” for addressing worker and human rights abuses,38

with some examples including the International Accord on Building and Worker Safety, the Pakistan Accord, now signed by over 100 brands,39

the Dindigul Agreement,40 the legally binding agreement between brands and IndustriALL in Cambodia supporting collective bargaining

and improved wages,41 and the Fair Food Program developed by the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. Common to all of these programs

are some or all of these WSR principles, which also generally form the backbone of the most effective oversight

initiatives: (1) they are led by workers or their representatives, (2) they are supported by binding and enforceable agreements between

workers and brands, (3) suppliers have financial incentive and capacity to comply, (4) they include mandatory consequences for non-compliance,

(5) they have measurable and timely outcomes for workers, and (6) they rely on rigorous and independent monitoring.42 Participation

in a binding agreement or one of these models would hold Nike accountable to support remedy in high-risk countries.

_____________________________

34

https://www.workersrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/WRC-Factory-Investigation-Findings-at-Violet-Apparel-Cambodia.pdf

35

https://media.business-humanrights.org/media/documents/Nikes_response_to_Ramatex_and_Hong_Seng.pdf

36

https://media.business-humanrights.org/media/documents/Nikes_response_to_Ramatex_and_Hong_Seng.pdf

37

https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/olympics-2024-investors-and-activists-urge-nike-to-settle-debt-with-workers/

38

https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2016/12/end-visit-statement-united-states-america-6-16-december-2016-maria-grazia?LangID=E&NewsID=21049;

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6055c0601c885456ba8c962a/t/61d5d71907ef68040bbc8602/1641404186331/ReStructureLab_InvestmentPatternsandLeverage_November2021.pdf

; https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2021-Aug/CBP%202021%20VTW%20FAQs%20%28Forced%20Labor%29.pdf;

https://blog.dol.gov/2022/01/13/exposing-the-brutality-of-human-trafficking;

https://rfkhumanrights.org/person/lucas-benitez/;

https://wallenberg.umich.edu/medal-recipients/2023-lucas-benitez/.

39

https://internationalaccord.org/100-global-brands-commit-to-pakistan-accord/

40

https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/comply-chain/steps-to-a-social-compliance-system/step-3-develop-a-code-of-conduct/

example-in-action-dindigul-agreement-addresses-sexual-and-gender-based-violence-sgbv-risks-related-to-wro

41

https://www.industriall-union.org/industriall-and-global-brands-sign-legally-binding-agreements-supporting-collective-bargaining-and

42

https://wsr-network.org/what-is-wsr/statement-of-principles/;

https://fairfoodprogram.org/; https://electronicswatch.org/new-worker-driven-remedy-principles_2635094.pdf

Evidence of the effectiveness of these programs

is clear in their ability to increase worker productivity, reduce risk, deliver meaningful human rights outcomes, particularly related

to health and safety, and enable remediation. For example, the Dindigul Agreement, a binding agreement

signed by PVH, H&M, and the Gap to protect garment workers at one factory in India, proved to “increase worker efficiency by

16%, increased reporting to work on time by 4.3% and has reduced attrition rate by 67% between 2021 and 2022.”43 Similarly,

since the Bangladesh Accord’s inception in 2013, “inspectors have identified more than

122,000 safety violations at covered factories. . . the overall rate of safety hazards identified in the original round of inspections

that have been reported or verified as fixed had reached 90%. More than 470 factories had fully remediated all violations and 934 factories

had completed at least 90% of the required repairs and renovations. More than 300 joint labor-management Safety Committees have been created

and trained to monitor safety conditions on an ongoing basis and the Accord’s complaint mechanism has resolved more than 290 safety

complaints from workers and their representatives.”44 Brands participating in the Bangladesh Accord also benefit

from high-quality inspections by independent auditors. In additional evidence of impact for workers,

from April to December 2022, workers using the provisions of the Dindigul Agreement at the participating factory raised 185 grievances:

177 (96%) were raised by women, 98% of the 185 grievances workers raised at the factory were resolved (90% of these were resolved within

a week). Shop floor monitors were trained to identify gender based violence and accompany workers in the grievance process.45

These models,

which are binding, ongoing, and include accountability for non-compliance, can be differentiated from Nike’s Employee Well Being

(EWB) surveys or online training modules for suppliers.46 Nike indicates that “all strategic suppliers have deployed

the EWB survey at least once” and it is not clear if or how the surveys improved worker well-being. Instead, it appears these efforts

are monitoring engagement with the tools, not improved outcomes for workers. This apparent one-way, once a year communication

channel, which lacks evidence of meaningful outcomes or follow-through on reported complaints, is different in terms of the risk management

and effectiveness and impact for workers from a WSR system designed by workers, for workers, with worker to worker training, independent

monitoring, and effective remediation.

Conclusion

With one of the largest

supply chain footprints in the apparel sector, Nike has exposure to many sourcing areas that could be considered as high-risk countries.

Traditional HRDD, and in particular social audits, are often insufficient to mitigating risk of exploitative labor practices and remediating

harms to workers in such high-risk contexts.

It

is not clear that Nike has a differentiated approach with enhanced HRDD for these areas that is sensitive to the operating business context

and restrictions on workers’ rights and is appropriately tailored to the intensity and severity of the human rights risks, with

appropriate methods to prevent and mitigate negative impacts.47

While

Nike has some methods and risk assessments to identify high-risk suppliers,48 the lack of enhanced approaches for ensuring

respect for human rights in high-risk sourcing countries. Its current reliance on audits and online surveys can undermine Nike’s

efforts to translate corporate practices into tangible improvements for workers and meaningful risk mitigation, which in turn may further

expose shareholders to reputational, legal, financial and operational risks that can negatively impact long-term shareholder value.

_____________________________

43

https://globallaborjustice.org/portfolio_page/dindigul-agreement-year-1-progress-report/

44

https://wsr-network.org/success-stories/accord-on-fire-and-building-safety-in-bangladesh/

45

https://globallaborjustice.org/portfolio_page/dindigul-agreement-year-1-progress-report/

46

https://purpose-cms-preprod01.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/20180814/EWB-White-Paper_FINAL.pdf

47 UNGP 14

and 17.

48

https://media.about.nike.com/files/2fd5f76d-50a2-4906-b30b-3b6046f36ebf/FY23_Nike_Impact_Report.pdf

Therefore, we believe

that shareholders would benefit from a report evaluating how implementing WSR principles and supporting binding agreements would impact

the Company’s ability to identify and remediate human rights issues in sourcing from high-risk countries.

Lastly, we note that

Nike recently announced a mass layoff affecting 2% of its total workforce.49 Public reports reveal that the sustainability

team has been disproportionately impacted, with a 20% reduction in its staff.50 This cutback could suggest that Nike’s

dedication to sustainability has diminished, which may affect the Company’s ability to uphold its ESG commitments, including those

related to human rights. Given the growing global push for mandatory due diligence legislation, and ongoing controversies affecting Nike’s

supply chain, sustainability staff reduction may raise concerns about the Company's future approach and ability to respond to these crucial

issues.

For these reasons,

we urge Nike’s shareholders to vote FOR PROPOSAL NUMBER 6 Regarding Worker-Driven Social Responsibility

Any questions regarding

this exempt solicitation or Proposal Number 6 should be directed to Sarah Couturier-Tanoh, Director of Shareholder Advocacy, SHARE at

scouturier-tanoh@share.ca.

THE FOREGOING INFORMATION MAY BE DISSEMINATED TO

SHAREHOLDERS VIA TELEPHONE, U.S. MAIL, EMAIL, CERTAIN WEBSITES AND CERTAIN SOCIAL MEDIA VENUES, AND SHOULD NOT BE CONSTRUED AS INVESTMENT

ADVICE OR AS A SOLICITATION OF AUTHORITY TO VOTE YOUR PROXY. THE COST OF DISSEMINATING THE FOREGOING INFORMATION TO SHAREHOLDERS IS BEING

BORNE ENTIRELY BY THE FILERS. PROXY CARDS WILL NOT BE ACCEPTED BY ANY FILER. PLEASE DO NOT SEND YOUR PROXY TO ANY FILER. TO VOTE YOUR

PROXY, PLEASE FOLLOW THE INSTRUCTIONS ON YOUR PROXY CARDS.

This is not a solicitation of authority to vote

your proxy. Please DO NOT send us your proxy card as it will not be accepted.

_____________________________

49

https://www.cnbc.com/2024/02/16/nike-to-lay-off-2percent-of-employees-cutting-more-than-1500-jobs.html

50

https://www.csofutures.com/news/nike-slashes-sustainability-staff/

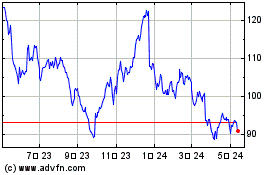

Nike (NYSE:NKE)

過去 株価チャート

から 7 2024 まで 8 2024

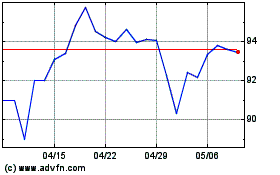

Nike (NYSE:NKE)

過去 株価チャート

から 8 2023 まで 8 2024