By Dave Michaels

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (September 12, 2020).

A government crackdown on traders accused of price manipulation

faces one of its biggest tests next week, as a pair of former

Deutsche Bank traders face trial on charges related to rigging

precious-metals prices using a strategy known as spoofing.

Traders at Citadel Securities and Quantlab Financial, high-speed

trading firms that use models to automate their buying and selling,

are among the witnesses scheduled to testify against the

ex-traders, James Vorley and Cedric Chanu. The criminal trial will

take place in Chicago with protocols aimed at reducing the risk of

coronavirus spread, including the use of masks and a requirement to

maintain social distancing.

The Justice Department has lost two of three prior trials over

spoofing, a type of price manipulation that involves bluffing other

traders into thinking supply or demand has changed.

Prosecutors have faced hurdles on their way to the latest trial,

with the judge in the case expressing skepticism in recent weeks

about whether evidence supports the claims of fraud.

"There is probably some additional pressure to win this one,"

said Aitan Goelman, a partner at Zuckerman Spaeder LLP who is a

former senior regulator and federal prosecutor. "I don't think that

means if they lose, they will never bring another spoofing case.

But they have not had a particularly successful run so far in

prosecuting spoofing."

One concern is persuading a jury that bluffing is actually

fraud. The traders argue they made no false statements -- usually a

precondition for fraud -- by sending orders they wound up

canceling. The electronic orders didn't convey any intent or

promises, the traders say, likening it to a poker player who bluffs

by upping the ante but doesn't talk about what cards he holds.

Nonetheless, prosecutors have obtained eight guilty pleas from

other traders accused of spoofing, including one who is scheduled

to testify against the former Deutsche Bank duo. A Justice

Department spokesman declined to comment.

In one episode from 2009, Mr. Chanu exchanged chat messages with

another Deutsche Bank trader about spoofing, according to court

filings. The other trader placed and canceled within seconds a

flurry of orders to buy gold futures, helping Mr. Chanu sell gold

at a higher price. The other trader wrote: "Got that up 2

bucks...that does show you how easy it is to manipulate

sometimes."

"Basically you tricked alkll [all] the algorythm," Mr. Chanu

replied in a message cited by prosecutors.

Spoofing involves sending orders that a trader doesn't intend to

have filled, essentially a feint designed to trick other traders

into posting prices the spoofer wants. Once spoofers accomplish the

trade they wanted, they cancel the orders that caused the market to

move in their favor.

Messrs. Vorley and Chanu, who worked in London, were charged in

2018 with wire fraud and conspiracy, but not spoofing. Much of the

trading at issue dates from 2009 through 2011, when spoofing could

have been considered illegal but wasn't yet defined in federal law.

Congress explicitly outlawed spoofing in the 2010 Dodd-Frank

financial overhaul law.

Attorneys for Messrs. Vorley and Chanu declined to comment.

"In some ways it feels like the department is trying to fit a

square peg into a round hole" by charging fraud and not spoofing,

Mr. Goelman said. "But I do think the government can make a case

there is an element of deception there. Just the fact that spoofing

is now illegal means it might be easier to prove a fraud case."

The Justice Department's fraud section has carved out a niche

prosecuting the cases, charging nearly 20 defendants since

2015.

Some critics have questioned whether spoofing should be

prosecuted as a crime, instead of a civil regulatory violation

handled by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Deutsche Bank

paid $30 million in 2018 to settle CFTC claims tied to the traders'

spoofing. Other experts say the Justice Department's attention is

warranted because manipulation affects commodity prices as well as

correlated assets, such as stocks.

"It is basically lying to people about their willingness to

trade and lying about the liquidity in the market," said James

Angel, a finance professor and regulatory expert at Georgetown

University's McDonough School of Business.

Repeated many times over, spoofing can be profitable, although

traders fighting the Justice Department say the losses they are

accused of causing are limited. In a separate case that could go to

trial next year, the alleged spoofing by two former Bank of America

traders caused losses for other traders of about $300,000 over

seven years, according to court filings.

In a filing made early this month, prosecutors outlined the role

of another former Deutsche Bank trader who plans to testify about

his colleagues' conduct. That trader, David Liew, pleaded guilty in

2017 and will testify that he learned to spoof by watching Messrs.

Vorley and Chanu, according to court filings. An attorney for Mr.

Liew and a Deutsche Bank spokesman declined to comment.

Traders at Citadel Securities and Quantlab are expected to

testify that bluffing is fraud because traders assume orders are

genuine, and not a feint designed to achieve something else. A

spokeswoman for Citadel Securities declined to comment, as did a

spokesman for Quantlab.

The mechanics of the trial have been modified in light of

concerns about the spread of Covid-19. Federal courts around the

country -- most of which shut down or severely limited operations

in March -- have taken various precautions to address the pandemic,

with some even postponing jury trials until next year. The

Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts published a guide in June

to help judges navigate through the thicket of public-health

concerns.

The case was filed in Chicago because CME Group Inc., which

operates the exchanges used by Messrs. Vorley and Chanu, is based

there. Potential jurors for the trial won't approach the judge's

bench during the jury-selection process and will instead wear

headsets to answer questions from the judge and attorneys. Those

who are picked will be spread across half of the courtroom in order

to force social distancing, and will deliberate in a separate

courtroom instead of meeting in a smaller jury room.

Write to Dave Michaels at dave.michaels@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 12, 2020 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

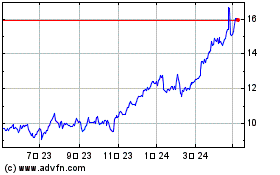

Deutsche Bank (TG:DBK)

過去 株価チャート

から 3 2024 まで 4 2024

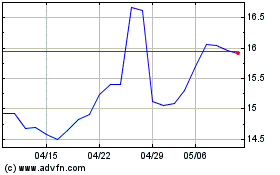

Deutsche Bank (TG:DBK)

過去 株価チャート

から 4 2023 まで 4 2024